<< Learning Center

Media Accessibility Information, Guidelines and Research

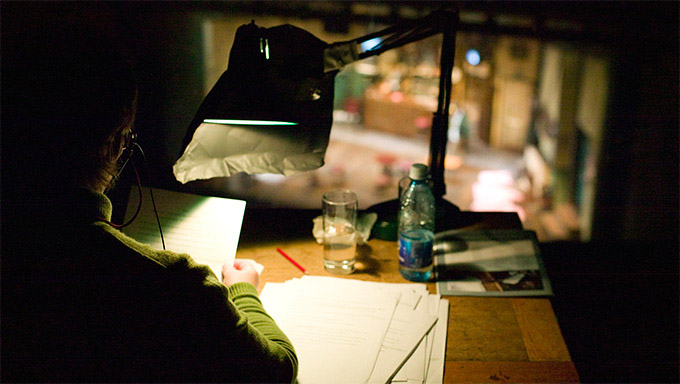

A Day in the Life of an Audio Describer

By Kelly Warren

The Process of Describing

My dog, Jack, erupts from his perch on the stairs to bark at the UPS man who just dropped off the package of flash drives from the Described and Captioned Media Program (DCMP). I’ve been expecting these five videos so I can begin the audio description (AD or description) process.

The DCMP sends their contracts-for-bid to vendors with videos listed by title, producer, runtime, grade level, and indication of the need for transcription. I receive each video on a flash drive and then upload it to my computer. If no script is provided, I’ll need to transcribe as well as describe. I do both these tasks as I watch the video the first time through. I have tested my system whereby I first watch the video and then describe, but I found it much more time efficient to describe and transcribe during my initial viewing, much like the way a person will watch it.

Editor's Note: This post was written in 2011. DCMP currently sends and receives files electronically.

Audio description is using additional audio narration for video (and television/film) that describes key visual elements that are not reflected in the original dialogue. Narration is inserted into the program’s natural pauses in clear, concise, and objective language. This might include a description of a shadow standing behind a door with a knife in hand, or a dream sequence that’s imperative to the plot.

Description on DCMP videos, delivered primarily through Internet streaming, is a userselectable option. On television it is typically provided through the Secondary Audio Programming (SAP) channel that can be switched on/off with a button located on the TV or remote control. In a few movie theatres scattered around the states, selected seats are wired with headphones to the soundtrack with the added description. While description was originally designed for people with vision loss, millions of others may also benefit from the concise translation of key visual components

Creating Good Description

To provide quality service, I rely on input from visually impaired viewers who like a voicer with a soft voice who doesn’t talk over the narrator. They also prefer clear, short, objective descriptions.

I also refer to guidelines in the Description Key, produced by the DCMP, the American Foundation for the Blind, and a team of experts in media description and education, that provides a framework for ensuring consistency and quality.

In producing good audio description, it’s all about “time.” Often, I get only a few seconds between the dialogue/narration to describe a scene; I have to get in and out without stepping on the narrator. But obviously the description has to be comprehensible. When describers run a time compression to speed up the voice on an already tight sentence, it’s sometimes impossible to understand what is being said. Such situations demand the art of word-smithing and use of good judgment; either shorten the description, work it in later, or leave it out altogether. While it’s sometimes impossible to describe everything of importance, a describer should keep in mind that a story unfolds over time. There’s no need to provide the viewer with all details at once.

When I finish the first draft, I have the advantage of knowing how the story unfolds, so I can go back and edit if I need more (or less) description. I find that I tend to over-describe on the first round. Once complete, I review my description and soundtrack with an emphasis on listening. I ask myself, “Can the soundtrack stand alone?” “Could someone follow this story if the screen was dark?”

Following is an instance where I had a luxurious 2-minutes to describe the opening montage of images from the documentary, Imaginary Enemy with only by a music bed for sound. I edited the segment here, for time:

“. . . now, a series of color film footage from the 1960’s: American military men prepare an artillery gun; Chinese military with horses, one horse wears a gas mask; a young teenage boy sits alone and draws; . . . Chinese men in a long line of trucks don gas masks as a military drill; young Chinese soldiers put on dark, round protective glasses; . . . a famous image of an atomic bomb where a row of trees bend over and back within a thick cloud of dust; the boy continues to paint his missile; now, dirt roils over the ground and in the trees from the intense blast. And, finally, the site of rocket launch . . . .”

Client Relationships and Bidding

My first description job was for the Wisconsin Council of the Blind. We created a 13-minute promotional video from a set of black and white photos of visually impaired people at their jobs. I decided on a male voicer and on myself to create the description. It turned out well, except for the videographer who walked off the job because he couldn’t wrap his head around the description, arguing that it wasn’t necessary to describe something that was on the screen because I was only repeating it. That experience taught me that some people cannot separate the act of seeing from that of hearing.

Also, I find it difficult to submit a bid for describing a video I have not seen. Payment rates are often based on the video’s total running time (TRT). In my opinion, previewing the media to determine the amount of time required for describing it is essential. In addition, the client should always provide information concerning the format type (documentary, animation, feature, or instructional) and special considerations such as foreign language with subtitles.

Knowledge of whether subtitles are present is relevant, because it takes time to voice them with similar inflexion and then mix the audio to match the person talking. Recently, I described and transcribed the documentary, Imaginary Enemy where the Chinese artist, Liao Yibai, spoke to the camera throughout the 23-minute video. Even though he spoke English, his speech was not discernable, so all his speech was subtitled and needed to be read in the description. This is an example where previewing the video would have been helpful before submitting a bid. If previewing is not efficient or workable with a client, then the describer should request as much information about the video as possible.

Future of Audio Description

The National Eye Institute says “blindness or low vision affects 3.3 million Americans age 40 and over, or 1 in 28. This figure is projected to reach 5.5 million by 2020” (NEI, 2004). So, we can expect a growing demand for audio description.

In October 2010, President Obama signed into law the Twenty-First Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act. The video description rules require ABC, CBS, Fox, and NBC affiliates in the top 25 market areas and cable and satellite television providers with more than 50,000 subscribers to provide video description. So soon, ABC, CBS, Fox, NBC, USA, the Disney Channel, TNT, Nickelodeon, and TBS will each be required to provide 50 hours of videodescribed prime time or children’s programming per calendar quarter. These new rules will go into effect July 1, 2012.

Editor's Note: The video description requirement expanded to the top 60 markets beginning July 1, 2015, and increased to 87.5 hours per-quarter effective July 2018 (but can now be scheduled any time between 6:00 a.m. and midnight, rather than only primetime or children's programming). As of the current policy, Nickelodeon and Disney Channel have since been displaced by History and HGTV on the top five non-broadcast channels, respectively.

Source: Wikipedia, "Twenty-First Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act of 2010"

The inherent issue with AD for television, film, and video is that it is a retrofitted effort, an afterthought and outside the film director’s oversight. Some directors complain that description misses the intent of the action on the screen. The added description is often considered an interruption; it sounds intrusive and is even a distraction for some. While this is the best we can offer right now, it is possible to do better.

We should expect that the users of AD will demand that their entertainment be of high quality, and not with the problems of intrusion and distraction. We need to take the Universal Design approach where AD is considered at the conception of the production process.

We need more directors and screenwriters to produce ‘descriptive scripts’ or ‘built-in’ audio description into their productions. Audio describers should be part of the production team as screenplay editors or reviewers. Describers should be present in the beginning. Where are the directors/screenwriters who will do this? I mean, if you were an independent filmmaker, wouldn’t you want to create a niche where both sighted and visually impaired people can sit side-by-side in the theatre and enjoy your film?

Think of the millions of visually impaired people who have eliminated movie-going from their lives because they cannot see the details on the screen. ‘Built-in’ description can be done in a way so that it is not so literal for the sighted person, and the visually impaired user will definitely notice and appreciate the added information. Moreover, there is room in the marketplace for both built-in description and AD as we know it today.

We have a long way to go in improving audio description for the masses. Just look at closed captioning—it started out with a similar federal mandate and it now appears on every television in every bar.

Finally, there are new audio describers coming onto the scene in response to the FCC mandate. Here’s my advice to you: listen to many different describers and examples of description; listen to the writing; listen to the voice quality and delivery. Does the description flow with the narration? Is the voice a good match with the narrator? Can you follow along with the screen off? Is the description edit and mix done well?

If you’re like me and like to problem solve on a minute scale, play with words, and can listen with your eyes, then you’ll enjoy being an audio describer. Welcome, good luck, and let’s get to it!

We’ve got a lot of work to do.

References

"Vision Loss From Eye Diseases Will Increase As Americans Age." National Eye Institute. National Eye Institute, 12 Apr 2004. Web. 24 Oct 2011. www.nei.nih.gov/news/pressreleases/041204.asp.

About the Author

Kelly Warren, owner of Mind’s Eye Audio, in Madison, WI, has 15 years of experience in audio productions. Contact her at kelly@mindseyeaudio.com. For more on the Universal Design approach to audio description, see the research paper, “The Rogue Poster-Child of Universal Design: Closed Captioning and Audio Description,” by John-Patrick Udo and Debra I. Fels, Ryerson University. 2009.

Tags:

Please take a moment to rate this Learning Center resource by answering three short questions.