<< Learning Center

Media Accessibility Information, Guidelines and Research

The Logic of the Motion Picture in the Classroom: Films in Schools for the Deaf (1915–1965)

By Bill Stark

Motion pictures have been a powerful medium for entertainment since their inception. In 1915 The Birth of a Nation grossed an amazing $10,000,000. Deaf persons loved silent films, as the visual quality was often extremely high (especially for those produced in the 1920s), and actors stressed the use of body language and facial expression.

The silent movies created the largest mass audience for public entertainment in the nation's history, and for a brief time the deaf community participated fully in the mainstream of this popular cultural form. Not only could Deaf people enjoy silent movies on a par with the hearing audience (with the exception of the piano accompaniment), but Deaf actors had an equal opportunity to earn a livelihood by appearing in them. After all, the audience could not distinguish hearing from Deaf actors, nor did the actors have to react to spoken cues.1

When silent films were released in 16-mm format, their use was initially aimed at the home enthusiast. But from the earliest days, 16-mm films, for both education and entertainment, made inroads to residential schools for the deaf. In 1915 the New Jersey School for the Deaf scheduled a moving picture series on Thursday evenings for students to see reels about San Francisco, nature study, book-making, and other subjects, and at least a dozen other schools had projectors. 2 George Propp reported concerning the time he was a student at the Nebraska School for the Deaf:

The first arc projected 16-mm educational film I ever saw was around 1930. It was a film developed by the Department of Agriculture for use by county agents on the use of electricity on the farm. The athletic coach, with access to athletic funds, probably was occasionally able to schedule an athletic demonstration film which was borrowed for a small fee from the nearby university film library. The showing of a 16-mm film, such as Chronicles of America, was such a momentous occasion that they were usually shown to the entire student body in an assembly program.3

But Hollywood never meant to accommodate deaf audiences—it just happened. Good silent films told their stories without words, and when they succeeded, teachers had an excellent basis for a transition to learning both language and content. It was particularly unfortunate this potential was lost as the technology developed a voice in the late 1920s, and the irony of the words that actor Al Jolson spoke in the 1929 "talkie" The Jazz Singer was not lost on teachers: "You ain't heard nothin' yet." Schools struggled on without this resource, and it is clear that the "demise of the silent film represented an educational tragedy for deaf children."4

One of the five deaf actors who lost their jobs with the advent of sound, Emerson Romero, decided to do something about it, and in 1947 he tried a technique involving the insertion of captions between the frames of a sound film. Others, including teachers and school administrators, were also busy searching for a solution. Dr. Ross Hamilton, assistant superintendent at the Lexington School for the Deaf (New York), utilized a technique developed in London, etching captions on glass slides and projecting them simultaneously onto a second, smaller screen at the lower left of the main screen. These did not prove to be practical techniques, but a process developed in Belgium for etching captions directly on film caught the attention of two school superintendents.

Film Access Becomes Law of the Land

These two key figures in the development of captioning in America were Dr. Edmund Burke Boatner, superintendent of the American School for the Deaf, and his friend, Dr. Clarence O'Connor, superintendent of the Lexington School for the Deaf. In 1949 they started Captioned Films for the Deaf (CFD) as a private film captioning company, depending on gifts and donations for support. It is well-documented that they later lobbied for federal support, and CFD became Public Law 85-905 in 1958 for the captioning of films "which play such an important part in the general and cultural advancement of hearing persons."5

Not as well-documented, though, is the fact that they lobbied from the very beginning to not only bring deaf persons back into the mainstream of movie entertainment, but also for the captioning of educational films. Dr. O'Connor's librarian at the Lexington school was Patricia Cory, who, in 1960, wrote School Library Services for Deaf Children,6 noting the American Association of School Librarians' recommendation that school librarians should supplement books with newer media developed to aid learning—that included seeking out motion pictures in all possible subject fields, for all age levels. But for deaf children, Cory noted that too heavy a burden was often placed on the sound track to transmit meaning in films. For a teacher of the deaf, a sound film was rarely useful, requiring extensive pre-teaching to derive any meaning and having characters who often spoke with their backs to the camera. "Even when they face the camera, dialogue is so rapid it could not be lipread."7 To fill this critical need, Boatner and O'Connor needed a sponsor for new legislation to support an amendment to the captioning law, an amendment authorizing the captioning of educational films.

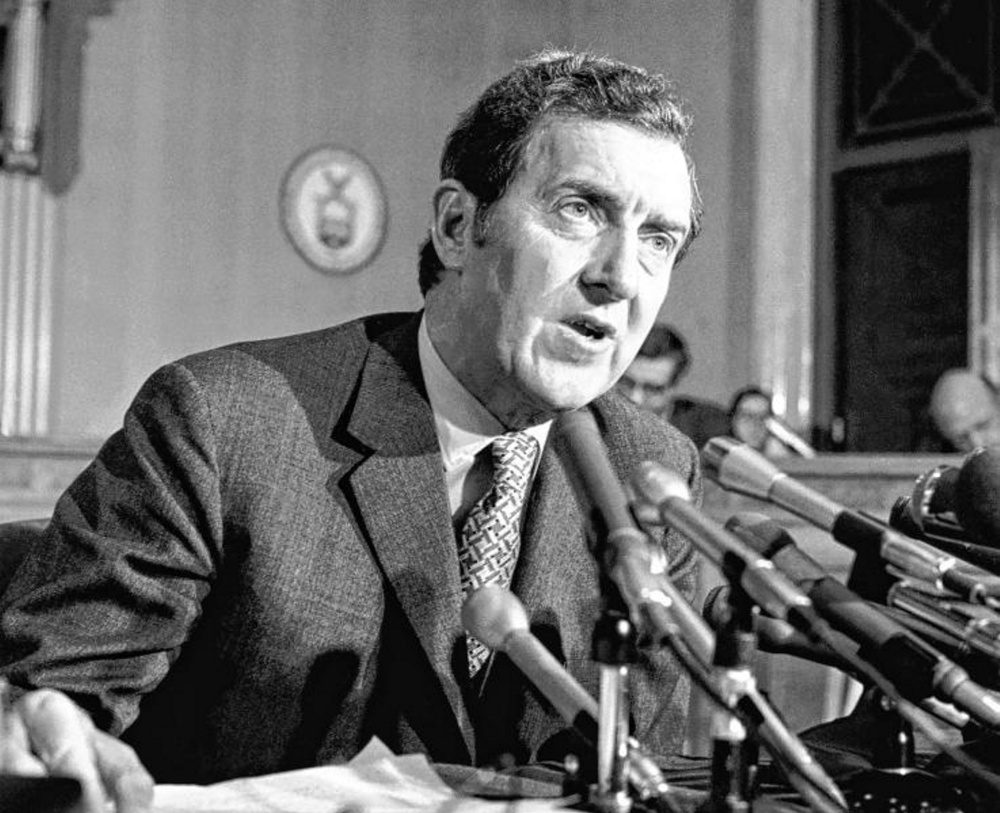

They found one in young Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine, described as, "six-feet four, powerful voice, big head, very imposing, and could be an intimidating figure."8 Though in the Senate only four years, Muskie was already an important figure in our country's politics, developing a reputation as an expert in writing and enacting legislation. Enlisting the co-sponsoring support of Senator Claiborne de Borda Pell of Rhode Island, in 1962 he introduced legislation which would impact the educational outcomes of tens of thousands of students who were deaf or hard of hearing.

During the special subcommittee hearing concerning this bill, Senator Muskie emphasized the need to aid the education of deaf children:

The more I have studied the potential of new methods, particularly audiovisual aids, the more I have become convinced of the tremendous possibilities of this method in teaching the deaf. The need for expanded educational opportunities for the deaf increases, and the time has arrived to take some positive action to assist these handicapped persons. Commercial firms are not interested in producing captioned films because of the limited market. They are also not interested in exploring new techniques in the use of films for this special group. The film industry is not in a position to promote teacher training in more effective use of the films.9

Muskie garnered the support of numerous educators, school administrators, and producers of educational films. Maurice B. Mitchell, president of Encyclopedia Britannica Films, Inc., noted: "The logic of the motion picture in the classroom is so apparent as to almost make it unnecessary to labor the point."10 But government support was needed to bring this crucial accessibility to students with a hearing loss, as film producers were not willing to make any investment of capital into the venture.

The bill quickly passed, becoming Public Law 87-715.11 It constituted an amendment to the 1958 authorization, adding a mandate to "promote the educational advancement of deaf persons" as well as to carry on research, training, production, acquisition, captioning, and distribution of educational and training films, increasing the minimum annual appropriation from $250,000 to $1.5 million.

Muskie resumed his illustrious career, which included a seven-year stint as chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Budget, serving as Democratic nominee for U.S. Vice President in 1968 and a candidate for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination, and accepting an appointment as U.S. Secretary of State in 1980. Senator Pell is best known for being largely responsible for the creation of Pell Grants in 1973, originally known as "Basic Educational Opportunity Grants," which provide financial aid to U.S. college students.

Providing the Access

While the technical process of film captioning was nicely developing, there was very limited experience in how to effectively write the language. It was clear early on that the audio in a film often transmitted more of the meaning than the visual. Compounding the problem was the fact that the language level of the narration was often too difficult for deaf children, and they could not assimilate all the information in so short a time.

Boatner revealed that in the American School's experience in captioning films, they found they could use about eight words in a caption, using three lines without obscuring the visual image. On a feature-length picture this totals about 4,800 words or about 16 double-spaced typewritten pages to be read by the deaf persons seeing the film. He recalled that Gates had thought it dangerous to introduce more than one new word in 37 and commented on the difficulty of deducing meaning from the context. He referred to the efforts of Mrs. Wood's class to deduce the meaning of "appeal" from the context. Dr. Boatner called for experience, skill, patience, and experimentation in holding the captions down to a readable level while at the same time building vocabulary and aiming for some elevation of the reading level.12

Captions used on the old silent films were for the mass audience and were thought to have used a fifth- or sixth-grade language level. Since this was consistent with newspaper language levels, these levels became the working standard. But it was also hoped that the captioning would be done by people who were very knowledgeable of the children's language, and that they could reach a language level that was understandable, yet provided opportunity for vocabulary growth.

Further discussion touched upon sentences which run on through more than one scene, where to break such sentences, and the possible desirability of attaching a film leader containing explanatory captions at the beginning of a film. The latter idea was abandoned, but the first captioned educational film, Rockets: How They Work (1962) appears to generally follow these working guidelines. For three decades experienced teachers of the deaf performed the captioning, often heavily editing or omitting the film language to an extent that would be frowned upon today.

As the first group of films was captioned, it was determined that these films were to be distributed through a network of depositories that involved virtually every school for the deaf in the country. Bill Stark recalled that in 1964 a placement at the Illinois School for the Deaf (ISD) was:

…heralded in the school publication (The Illinois Advance) [for being] selected by Captioned Films for the Deaf, USOE, to become one of the educational captioned films depositories. Twenty-eight captioned films were to be housed in a room in the school's administration building called the audiovisual aids room. Media, especially for the deaf and geared toward the needs of the deaf learner, had become a reality!13

Lesson guides were also written for each educational film to ensure effective use. The preface to the first bound volume of lesson guides, written by educators at a workshop held at DePaul University in 1968, read as follows: "Even a good film can lose much of its effectiveness if not used properly. When films are not integrated with the curriculum, students are encouraged to transfer to educational films the passive attitudes developed toward entertainment films."14

The program was even authorized to distribute filmstrips and other software, along with equipment. CFD thus provided vital support for education of deaf students, and a debt of gratitude will forever be owed to the program and its leaders. While these developments were phenomenal, they were to receive a significant boost in 1965 with the passage of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). Largely because of CFD and ESEA support, Instructional Media Centers were developed in schools for the deaf. There was an addition to most residential schools' faculty of library/media specialists who became CFD depository managers for their respective schools.

Epilogue

With the introduction of videocassettes, CFD became Captioned Films/Videos (CFV) for the Deaf in 1984. Multimedia was added in 1991, and the program became the Captioned Media Program (CMP). The latest name change occurred in 2006 with the birth of the Described and Captioned Media Program (DCMP), which expanded services to include blind and visually impaired students through a newer media accessibility option known as description. DCMP provides not only a library of free-loan accessible media, but also a clearinghouse of educational media information and a center for training and evaluation of description and captioning service providers.

Since the first educational film was captioned in 1962, CFD, by all its names, has been at the forefront of leadership in the tremendous growth of accessible educational media. The foundation for this was laid during 1915–1965.

About the Author

Early in his career, Bill Stark was a CFD depository manager, film evaluator, caption writer, and lesson guide writer. He was taught how to caption in the 1970s by the late "father of closed captioning," Dr. Malcolm Norwood.

Continuing to assume more responsibility in the CFD/CFV program, he directed summer workshops for captioning and lesson guide writing, before becoming the CFV director in 1991 and then guiding the program through its changes to CMP in 1998 and DCMP in 2006.

Footnotes

-

1

Schein, Jerome. At Home Among Strangers. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 1989.

-

2

Schuchman, John. Hollywood Speaks: Deafness and the Film Entertainment Industry. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois

Press, 1988, pp. 45. Print.

-

3

Propp, George. "An Overview of Progress in Utilization of Educational Technology for Educating the Hearing Impaired." American

Annals of the Deaf, October, 1978, pp. 646-52. Print.

-

4

Schuchman, John. Hollywood Speaks: Deafness and the Film Entertainment Industry. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois

Press, 1988, pp. 23. Print.

-

5

Public Law 85-905. Described and Captioned Media Program. 1958. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Web. 5 Mar

2010. http://www.dcmp.org/caai/nadh212.pdf.

-

6

Cory, Patricia. School Library Services for Deaf Children: Audio-Visual Material. Described and Captioned Media Program. 1960.

Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf, Inc., Web. 5 Mar 2010. http://www.dcmp.org/caai/nadh103.pdf.

-

7

Ibid, pp. 4

-

8

Hunter-Gault, Charlayne. "Remembering Ed Muskie." Online NewsHour. 26 Mar 1996. Public Broadcasting Station, Web. 5 Mar

2010. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/remember/muskie_3-26.html.

-

9

Captioned Films for the Deaf, Hearing Before a Special Subcommittee of the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare. Described

and Captioned Media Program. 1962. U.S. Government Printing Office, Web. 5 Mar 2010. http://www.dcmp.org/caai/nadh248.pdf.

-

10 Ibid, pp. 6

-

11 Public Law 87-715. Described and Captioned Media Program. 1962. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Web. 5 Mar

2010. http://www.dcmp.org/caai/nadh243.pdf.

-

12 Cory, Patricia. "Report of a Conference on the Utilization of Captioned Films for the Deaf." Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare, 1960, pp. 8. Print.

-

13 Stark, Bill. "The Decade That Was: Birth and Growth of Media at the Illinois School for the Deaf." American Annals of the Deaf.

October, 1974, pp. 578-73. Print.

- 14 Lesson Guide for Captioned Films: A Training and Utilization Guide. Described and Captioned Media Program. 1968. Educational Media Corporation, White Plains, New York. Web. 5 Mar 2010. pp. 2. http://www.dcmp.org/caai/nadh104.pdf

Tags:

Please take a moment to rate this Learning Center resource by answering three short questions.