<< Learning Center

Media Accessibility Information, Guidelines and Research

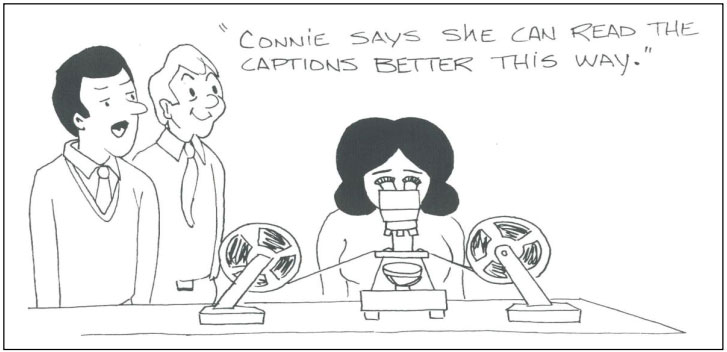

Captioned Films in Science

By Connie Nagy

[Editor's Note: This article was written in 1981 and has since been archived. Content may be out of date, but it is preserved in its original form.]

Connie S. Nagy is currently teaching science in the high school department of Illinois School for the Deaf, where she has taught for three years. Mrs. Nagy received her B.A. degree in chemistry from Gallaudet College in 1973. She received her M.A. degree in deaf education from Illinois State University in 1977. She has served as a caption writer for both the 1980 and 1981 Captioned Films for the Deaf summer workshops at Illinois School for the Deaf. In addition, she has served as a field film evaluator for the Captioned Films Program.

Many students, both hearing and deaf, have acquired a rather distorted image of science. To some of them, science class means memorizing many long, scientific words and being bombarded with scientific facts. These are the concepts of science. To others, science is like technology; it is a means of developing gadgets and appliances that make their lives more pleasant and comfortable. These are the processes of science. The concepts and the processes of science are important, but they need to be interrelated in the classroom. Such a balance will expose the students to science in a rightful manner.

To teach science concepts and to involve the students in the exciting process of inquiry and discovery, the science teacher should provide them with firsthand experience. To accomplish this, the teacher will need microscopes, chemicals, laboratory equipment, models, specimens for dissection, charts, science kits, and other tools. However, when it is not possible for students to obtain firsthand experience with materials and phenomena, the next best thing is to provide these experiences vicariously. The film is a teaching device that achieves closeness to reality more than any other device.

Teachers of the deaf in all subject areas realize the usefulness of captioned films. They are indeed a valuable means of imparting information. However, the method of utilizing a captioned film can make a difference between effectiveness and ineffectiveness. Captioned films are not films to be shown for entertaining or for keeping the students busy. Rather, their use should be as a planned, purposeful activity that fits into a classroom-learning situation.

As a high school science teacher, I have found captioned films for the deaf to be a valuable teaching aid. However, the entire value of any film may be lost if a teacher does not purposely plan for its use. If possible, the film should be previewed. Not only does this help to judge if the reading level and film content is suitable, but also it familiarizes the teacher with the film. This helps to anticipate questions the students might ask. Also, teachers learn from previewing films. Some information passed on in the film may be new to an inexperienced teacher and will add to that teacher's knowledge of the subject matter. Previewing may help the teacher feel less inept.

After previewing, the teacher should decide if the teaching unit will be based on the film or if the film will be used as a review to be shown at the completion of an already established unit. Many times, I prefer to use the film as a review because the students will then probably be more familiar with the vocabulary and the events in the film.

Before showing the film to students, I usually explain to them briefly, what the film is about. If the film contains a very interesting visual or shows an unusual scene, I announce this to the class.

This helps arouse their curiosity and leads to anticipation. Usually, if you give them something exciting to look for, they will be more attentive. For example, if the students know that actual autopsy specimens will be shown (Live or Die, CFD1245) or if they are informed that the unusual pseudopodic movements of the amoeba will be seen (A New Look at Leeuwenhoek's "Wee Beasties," CFD1080), their attention will probably be held in anticipation.

After the film has been shown, its effectiveness can be judged by the students' reaction to it. If questions are asked or discussions are started, the film will be listed in my card file of potentially useful films. If the class is dull or sluggish, I question the value of the film or the manner in which it was used.

More and more science films are being captioned every year. The science teacher needs to take time to preview them and see if they can be of use as part of the teaching strategies. Are they motivational? Do they yield the desired information? Do they produce the intended effect? Do they help teach the concepts and the process of science? If so, it is certainly worth the teacher's time to plan how these films can be best implemented into the science program.

Tags:

Please take a moment to rate this Learning Center resource by answering three short questions.