<< Learning Center

Media Accessibility Information, Guidelines and Research

Black Deaf Culture Through the Lens of History

By Benro Ogunyipe, Former NBDA President 2011-2013

- A Short Commentary on the History, Culture, and Education of Black Deaf People

- The Black Deaf Community: Recent Stories, Accomplishments, and Recognition

- Black ASL Content in Social Media

- Black Deaf Community and Black Lives Matter

- National Black Deaf Advocates

This article was written for the Described and Captioned Media Program (DCMP) Learning Center of accessibility information. DCMP also provides numerous Black History video resources to qualified teachers and parents, along with thousands of other educational accessible videos.

A Short Commentary on the History, Culture, and Education of Black Deaf People

Black Deaf people have one of the most unique cultures in the world. The Black Deaf Community is largely shaped by two cultures and communities: Deaf and African-American. Some Black Deaf individuals view themselves as members of both communities. Since both communities are viewed by the larger, predominately hearing and White society as comprising a minority community, Black Deaf persons often experience double prejudice against them in terms of racial discrimination and communication barriers. Black Deaf women may experience three strikes of prejudice against them due to their race, Deafness, and sexist practices that prevail in our male dominated culture.

These discriminatory practices can be traced back to the segregation era during the 17th to mid 20th centuries. Black Deaf individuals were not accepted in either the Deaf or the African-American community. Black organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the National Urban League were focused exclusively on fighting for equality and equal rights for the African-American community. The concerns of the Black Deaf community were not the focus of national civil rights organizations such as NAACP, SCLC, and the National Urban League. The Black Deaf community had no communication access with these national civil rights organizations and their leaders.

These discriminatory practices can be traced back to the segregation era during the 17th to mid 20th centuries. Black Deaf individuals were not accepted in either the Deaf or the African-American community. Black organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the National Urban League were focused exclusively on fighting for equality and equal rights for the African-American community. The concerns of the Black Deaf community were not the focus of national civil rights organizations such as NAACP, SCLC, and the National Urban League. The Black Deaf community had no communication access with these national civil rights organizations and their leaders.

The ideal fight for equal access would point to joining with Deaf organizations. Unfortunately, Black Deaf people were prohibited from joining Deaf organizations and clubs. The premier national advocacy organization for the rights of deaf people, the National Association of the Deaf (NAD), prohibited Black membership for 40 years until 1965, a year after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. From its founding in 1864 until 1950, Gallaudet College (now Gallaudet University), did not admit and graduate Black Deaf students. The college had its first Black graduate, Andrew J. Foster, in 1954 – the same year of the landmark Supreme Court case Brown vs. Board of Education decision.

From the 1870s until the 1970s, at least 15 states, mostly in the south, maintained separate schools for Black and White deaf students. Integration of Black and White students did not occur until after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision. In 2011, former Black Deaf students of the Kentucky School for the Deaf received long overdue diplomas once denied to them 60 years earlier because of the color of their skin. Because Black deaf students were prohibited from opportunities to interact with students and teachers on the White Deaf school campuses, this separation contributed to the development of Black ASL, a variety of American Sign Language that's distinctively different from those of white deaf students' signs.

From the 1870s until the 1970s, at least 15 states, mostly in the south, maintained separate schools for Black and White deaf students. Integration of Black and White students did not occur until after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision. In 2011, former Black Deaf students of the Kentucky School for the Deaf received long overdue diplomas once denied to them 60 years earlier because of the color of their skin. Because Black deaf students were prohibited from opportunities to interact with students and teachers on the White Deaf school campuses, this separation contributed to the development of Black ASL, a variety of American Sign Language that's distinctively different from those of white deaf students' signs.

According to Solomon (2018), "The Deaf club is essentially a Deaf person's second home, providing a place where the Deaf can come together, exchange ideas, develop friendships, participate in social events, and have the opportunity to attain a leadership position within the Deaf community. After World War II Black Deaf [people] found themselves in need of a place to meet so they began to form their own clubs, congregations, and organizations." Because of the denied acceptance and membership in Deaf organizations and clubs that were exclusively for white Deaf persons, Black Deaf organizations arose during the 1950s and 1960s in the urban cities with large numbers of Black Deaf residents such as Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC. At the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) Convention held in Cincinnati, OH in 1980, a group of Black Deaf leaders presented a list of concerns to the convention delegates. These included issues such as the NAD's lack of attentiveness to the concerns of Black Deaf Americans as well as the lack of representation of Black Deaf individuals as convention delegates. They specifically requested NAD to take action to communicate better with the Black Deaf community, encourage the involvement of minorities within the national and state organizations, and recruit more Black Deaf children in the Junior NAD and NAD Youth Leadership Camp, all of which hindered Black Deaf people's goal of achieving their full potential.

The course of history for the Black Deaf community began to take on a new direction in 1981 when a local committee in Washington, DC organized the Eastern Regional Black Deaf Conference at Howard University, and in 1982 at a national conference entitled "Black Deaf Strength through Awareness" held in Cleveland, Ohio. An important outcome of the conference was the establishment of a new organization, National Black Deaf Advocates (NBDA). The establishment of NBDA has spurred the growth of local chapters in Washington, DC, Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York City, Chicago, Detroit, Memphis, Atlanta, and many other cities. Currently, the NBDA has over 30 local chapters and sponsors a variety of programs such as leadership training programs for high school and college students, a Miss Black Deaf America Pageant, leadership opportunities at the local and national levels, workshops at regional and national conferences, and a scholarship program for deserving Black Deaf college students.

The course of history for the Black Deaf community began to take on a new direction in 1981 when a local committee in Washington, DC organized the Eastern Regional Black Deaf Conference at Howard University, and in 1982 at a national conference entitled "Black Deaf Strength through Awareness" held in Cleveland, Ohio. An important outcome of the conference was the establishment of a new organization, National Black Deaf Advocates (NBDA). The establishment of NBDA has spurred the growth of local chapters in Washington, DC, Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York City, Chicago, Detroit, Memphis, Atlanta, and many other cities. Currently, the NBDA has over 30 local chapters and sponsors a variety of programs such as leadership training programs for high school and college students, a Miss Black Deaf America Pageant, leadership opportunities at the local and national levels, workshops at regional and national conferences, and a scholarship program for deserving Black Deaf college students.

Bibliography:

- McCaskill, Carolyn. The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 2011

- Solomon, Andrea (2018): Cultural and Sociolinguistic Features of the Black Deaf Community. Carnegie Mellon University. Thesis. https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/6684059.v1

- Tabak, John. Significant Gestures: A History of American Sign Language. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2006.

The Black Deaf Community: Recent Stories, Accomplishments, and Recognition

Black Deaf People in New Leadership Positions

There have been significant hires and appointments of Black Deaf people to new leadership positions in the past few years. In the public sector, Earnest Covington III became the Executive Director of the Rhode Island Commission on the Deaf and Hard of Hearing; Benro Ogunyipe as the Executive Director of the Illinois Deaf and Hard of Hearing Commission; and most recently, Dr. Opeoluwa Sotonwa as the Commissioner for the Massachusetts Commission for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. In education, Ernest E. Garrett III became the Superintendent of the Louisiana Special School District (SSD); Shanae Rouse as the Director of High School at the Alabama School for the Deaf; and Alesia Allen as Assistant Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion at Rochester Institute of Technology's National Technical Institute for the Deaf. In the corporate sector, Storm Smith is the Producer of BBDO Worldwide; Claudia Gordon, Director of Government and Compliance at T-Mobile; Justin Folk, Vice President Finance of Folk Williams Financial Management, Inc.; Corey Burton, Director of ZVRS & Purple Communication’s Enterprise Video Solutions Account Management; and Isidore Niyongabo, Director of Human Resources at Convo.

New Additions of Black Deaf Individuals With Doctorate Degrees

Dr. David James and Dr. Glenn B. Anderson were the first Black Deaf persons to earn a doctorate in 1977 and 1982, respectively. Dr. Shirley Allen became the first Black Deaf woman to earn a doctorate in 1992. Today, there are now approximately 20 known Black Deaf scholars. Most notably, the new additions to the ranks are: Dr. Opeoluwa Sotonwa, Dr. Alesia Allen, Dr. Onudeah Nicolarakis, and Dr. Rezenet Moges-Riedel. Dr. Jenelle Rouse made history as the first known Black Deaf Canadian with a doctorate degree. Prospects for the future look promising with several Black Deaf candidates currently pursuing their doctoral degrees.

Dr. David James and Dr. Glenn B. Anderson were the first Black Deaf persons to earn a doctorate in 1977 and 1982, respectively. Dr. Shirley Allen became the first Black Deaf woman to earn a doctorate in 1992. Today, there are now approximately 20 known Black Deaf scholars. Most notably, the new additions to the ranks are: Dr. Opeoluwa Sotonwa, Dr. Alesia Allen, Dr. Onudeah Nicolarakis, and Dr. Rezenet Moges-Riedel. Dr. Jenelle Rouse made history as the first known Black Deaf Canadian with a doctorate degree. Prospects for the future look promising with several Black Deaf candidates currently pursuing their doctoral degrees.

Black ASL in News Media and a Documentary

Black American Sign Language (BASL) has gained more attention in the news media in the past few years. Major newspapers have featured Black ASL, including Washington Post, New York Times, and Los Angeles Times. Led by Dr. Carolyn McCaskill and Dr. Joseph Hill, authors of The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure (2011), Black ASL made its way into the television media and had its first documentary. The Signing Black in America documentary was screened in 2020 and aired on PBS stations in select cities, highlighting the history and development of Black ASL. Black ASL content crossed the border into Canadian TV and inspired Black Deaf Canadians to advocate for further research of BASL in the Canadian Black Deaf community.

The Fight for Integration of Black Deaf Education

A group of Black Deaf people campaigned to raise awareness about honoring the legacy of a Black mother, Louise B. Miller, who successfully sued the D.C. Board of Education in 1952 to have her child and Black Deaf students educated within the district. This U.S. District Court order led to the establishment of Kendall School Division II School for Negroes, a school which was segregated from the main Kendall school. The case was a precursor to the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown vs. Board of Education, which outlawed school segregation. The plaque commemorating Kendall School Division II School for Negroes is posted less visibly on the Gallaudet campus. Gallaudet is committed to the task of creating a memorial honoring Louise B. Miller, the 23 Black Deaf students, and four teachers of the Division II School. The story of the fight was documented in the film Class of '52, and the video can be viewed at DCMP.

The Story of the Last Segregated School for the Deaf

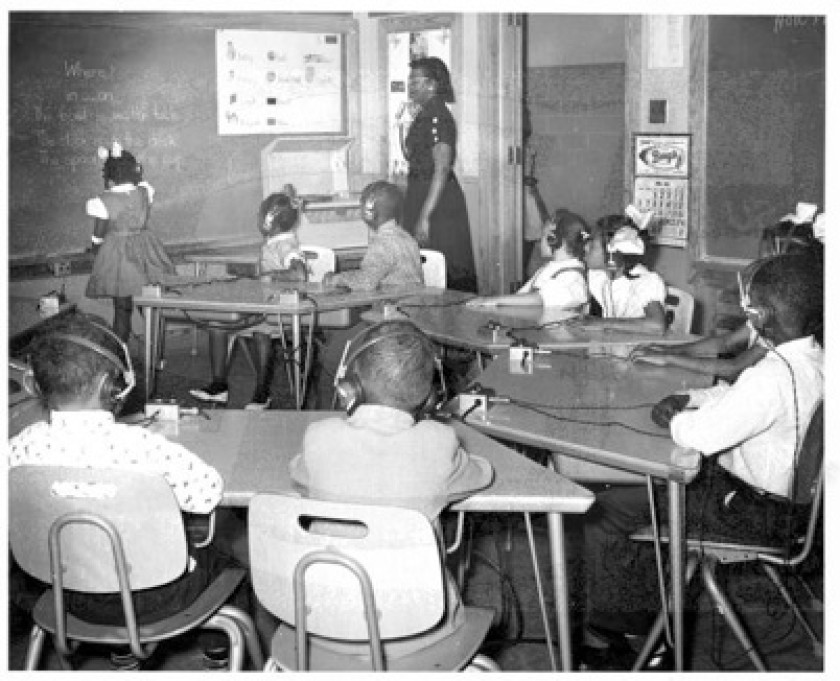

In 1978, Louisiana was the last segregated state school for the Deaf to become integrated in the United States. Sorenson Communications seized the opportunity to celebrate and honor four graduates of the Southern School for the Deaf (SSD) in Baton Rouge. Formerly known as Louisiana State School for the Colored Deaf and Blind (also Southern State School for the Negro Deaf), it was housed on the campus of Southern University, a member of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). The Black Deaf alumni of SSD shared the stories of their time at the school, their use of Black ASL in the classroom, and the Black Deaf experience in a five-minute short film, Black Deaf History – Southern School for the Deaf.

In 1978, Louisiana was the last segregated state school for the Deaf to become integrated in the United States. Sorenson Communications seized the opportunity to celebrate and honor four graduates of the Southern School for the Deaf (SSD) in Baton Rouge. Formerly known as Louisiana State School for the Colored Deaf and Blind (also Southern State School for the Negro Deaf), it was housed on the campus of Southern University, a member of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). The Black Deaf alumni of SSD shared the stories of their time at the school, their use of Black ASL in the classroom, and the Black Deaf experience in a five-minute short film, Black Deaf History – Southern School for the Deaf.

Black Deaf Center: The New Centralized Black Deaf Resources

In June 2020, a Black Deaf collaboration team led by the founder Tar Gilliam launched the Black Deaf Center website as a one-stop place for housing and sharing community resources regarding the Black Deaf experience. The BDC website includes documentaries and vlogs highlighting Black Deaf experience, educational books for all ages, a list of Black Deaf persons providing presentations and workshops, Black Deaf-owned businesses, connection with Black Deaf Youth, and more.

Center for Black Deaf Studies Established at Gallaudet University

In 2020, Gallaudet University established the first-of-its-kind Center for Black Deaf Studies (CBDS) as an outreach center for teaching and learning about the Black Deaf experience, and providing easy access to a range of useful content resources. Professor Dr. Carolyn McCaskill is serving as CBDS’s founding Director. One of the CBDS goals is to offer a minor focusing on the histories and cultures of African Americans with an appreciation for the historical, social, and political influences of Africa and the African diaspora.

Black ASL Content in Social Media

In April 2020, Nakia Smith, aka Charmay, created a TikTok account introducing five generations of her Black Deaf family and how they communicate in Black ASL. As a social media influencer of Black ASL content, Charmay made a series of educational and informative videos on the history and practice of Black ASL. Charmay’s video went viral, landing in a New York Times article, Black, Deaf and Extremely Online, and Blavity: TikToker Has Gone Viral For Putting The Culture On To Black American Sign Language. Additionally, Netflix requested Charmay to explain the difference between Black ASL and ASL.

Black Deaf Community and the Black Lives Matter

The majority of Black Deaf people identify more with their ethnicity than their deafness due to the shared struggle of racism and oppression experiences aligned with the African-American community. Black Deaf people across the United States took part in the Black Lives Matter movement following the death of George Floyd. Several news media covered Black Deaf people’s participation in the demonstrations, including a local TV news affiliate in Memphis, TN: Black Deaf Lives Matter Demonstrators Join Memphis Protesters Downtown. CBS News interviewed two Black individuals, a hearing interpreter and a Deaf leader: Making the Black Lives Matter More Accessible. One article examined the obstacles Black Deaf Americans face when dealing with the police. Two Black Deaf women, the multi-talented creative director Storm Smith and actress Natasha Ofili, wrote and produced a short film, Am I Next?, spotlighting Black Deaf individuals’ struggle that represents Black Deaf people’s experience navigating through systemic discrimination on the grounds of race on a daily basis.

National Black Deaf Advocates

National Black Deaf Advocates (NBDA) is the official advocacy organization for thousands of Black Deaf and Hard of Hearing Americans. For more than three decades, NBDA has been at the forefront of advocacy efforts for civil rights and equal access to education, employment, and social services on behalf of the Black Deaf and Hard of Hearing in the United States.

The organization's mission is "to promote the leadership development, economic, and educational opportunities; social equality; and to safeguard the general health and welfare of Black Deaf and hard of hearing people."

Founded in 1982, NBDA is a growing organization with more than 30 chapters across the country. As a non-profit organization, NBDA is supported by its members and others interested in furthering the mission, vision, and strategic objectives of this esteemed organization. Membership includes Black Deaf and Hard of Hearing; parents of Black Deaf and Hard of Hearing children; professionals who work with Black Deaf and Hard of Hearing youth and adults; sign language interpreters; people of color; and other interested individuals and organizations.

NBDA Executive Board serves on a voluntary basis and is comprised of a majority of Deaf and Hard of Hearing advocates, and governs National Black Deaf Advocates. The NBDA Board of Directors consists of officers elected during the national conferences, elected regional representatives from their respective regional conferences, and appointed board members.

For more information about NBDA, please visit our website: www.nbda.org.

NBDA and DCMP

Last, but not least, NBDA is greatly indebted to the U.S. Department of Education, particularly its Described and Captioned Media Program (DCMP), which provides valuable resources to enhance the educational success of our K–12 Black Deaf students and those who also experience varying degrees of vision loss. Their service also extends to interpreters and other professions serving those K-12 students. NBDA cannot do it alone; with programs such as the DCMP, we are confident that one day Black Deaf people can—and will—enjoy greater educational, economic, and social parity within mainstream society.

Archive

A previous version of this post from 2018 has been archived here.

About the Author

Benro T. Ogunyipe is the Executive Director of the Illinois Deaf and Hard of Hearing Commission. He served for 6 years as president, vice president, and chair of the board of National Black Deaf Advocates, Inc. He previously worked for the Illinois Department of Human Services as Senior Accessibility Specialist, Reasonable Accommodation Specialist, and Investigator of the ADA/Section 504 Discrimination Complaints for 17 years.

Benro T. Ogunyipe is the Executive Director of the Illinois Deaf and Hard of Hearing Commission. He served for 6 years as president, vice president, and chair of the board of National Black Deaf Advocates, Inc. He previously worked for the Illinois Department of Human Services as Senior Accessibility Specialist, Reasonable Accommodation Specialist, and Investigator of the ADA/Section 504 Discrimination Complaints for 17 years.

In 2014 and again in 2016, U.S. President Barack Obama appointed Benro to the National Council on Disability. Benro was also appointed by three different Illinois governors to public bodies and was an appointed board member of the National Association of the Deaf. He is a seasoned guest lecturer at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Disability Studies and Columbia College Chicago’s Interpreter Training Program on Multicultural Issues. Benro received a Bachelor of Arts degree from Gallaudet University and a Master of Public Administration (M.P.A.) degree from DePaul University, School of Public Service.

Benro Ogunyipe’s LinkedIn profile

To cite this article:

Ogunyipe, Benro. "Black Deaf Culture Through the Lens of History." www.dcmp.org/learn/366. Described and Captioned Media Program, n.d. Web.

Updated February, 2021